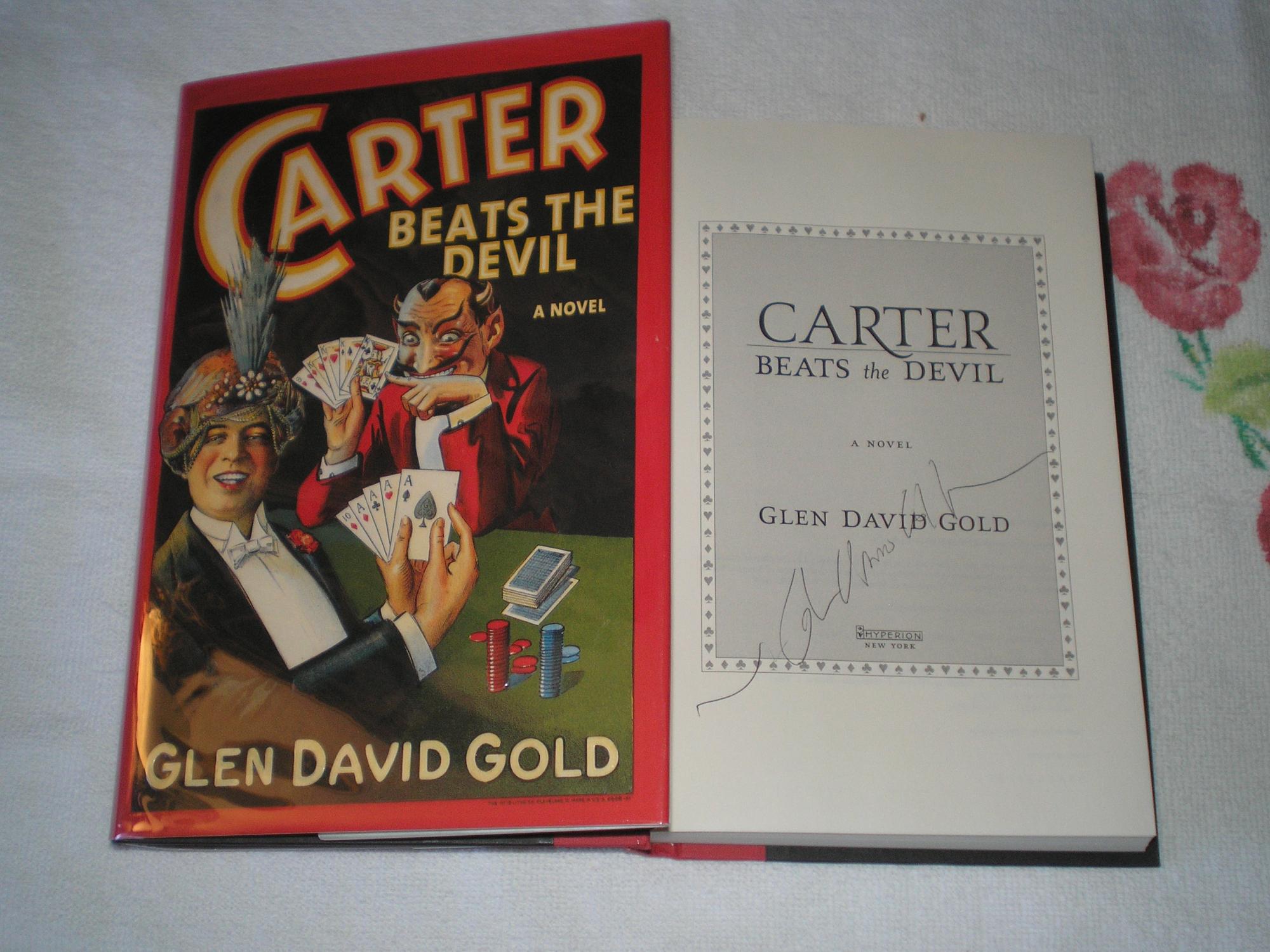

Nothing makes sense if you stand back and analyse it - but Gold allows no such luxury. The logic of events is always bizarrely random anyway. Yet the convolutions don't matter hugely. It's a novel that works on every level: as an evocation, an instruction, a revelation as fun.īecause conjurors guard their secrets, it's hard to tell too much of the plot without giving too much away - except to hint that we're at that cusp of the 20th century where television came to sweep vaudeville into oblivion. Since this is also, in part, a quasi-biography of Carter, we meet him young and set out on the dusty road of small-town touring with him, watching the rich boy with an ambition tinker with Kards and Koins till the moment of great illusions arrives.

What was Houdini like? How did he do what he did? The feisty little runt is given flesh.

He creates his own rich, strange world where anything is possible, where characters from fact and fiction mingle.Įvery one of these tricks - the vanishing elephant, the lion who becomes a man, the motorbike disappearing into thin air - comes rooted in fact. Stage illusions were a popular art they worked at pace, with drive and rolling drums. And his plot - garish, crude, infernally clever - is precisely honed to the task: it is a triumph of misdirection, a nest of boxes constantly springing fresh surprises. Cue much mayhem and hectic adventuring.īut Gold's real aim is to recapture the lost era of the great illusionists and escapologists, of Houdini, Thurston and Devant, to evoke the time when audiences believed what they saw a time when real magic was somehow possible and its prime purveyors were among the most famous people on earth. Two hours before some mysterious illness carries him off, Harding appears on stage with Charlie Carter the Great, master magician, and confides an awful secret to him. We begin and end in San Francisco, 1923, with the sudden death of Warren Gamaliel Harding (a US president to make George W Bush look imposing).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)